Dans Mon Oncle, nous voyons un homme curieux qui decouvrit que la vie c’est “moderne”. Et, “moderne” n’est pas “bien” tous les temps. Deux terres connaitent et essayer vivre ensemble. Pendant le film, c’est très dole, mais un peu triste parce que les personnages ne voie pas que se passe. L’homme avec un carrière constamment a mal humoraux. Sa maison et très beau mais c’est très géometrique et n’est pas facile chez vivre. L’homme–l’oncle–sans travaille est très heureux. Il apporte heureusement tous les endroits qu’il visite. La famille de la maison moderne est comme la cuisine de la maison : la fontaine, le garage, la cuisinere tout sont dangereux!

The Modern House: living monster?

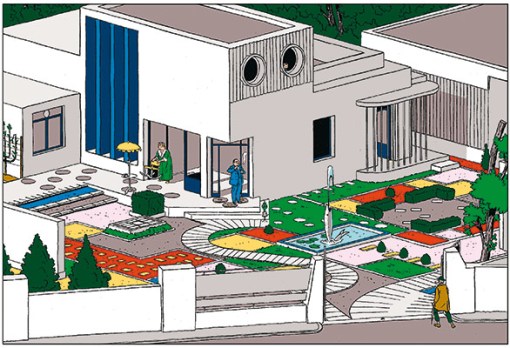

The Modern House, full of all its amenities—which seems quite a scary word that must necessarily be included in an sterile and salesmen-like discussion of appliances—is a threatening place. Electrocution, hypothermia, and scalding are a very few of the accidents we face in our daily hygienic routine. In no other era than the sixties, perhaps, we find the looming apocalypse of our own invention encroaching on our sacred spaces. The places we eat. The places we undress. The places we converse. The places we make love. They are now filled, as Mon Oncle charmingly demonstrates, with abstract visions of man’s achievements: liberation from organic dependency on our environment. In the ultimate irony, we have risen above the dirt to be forever enmeshed in electrons.

The Organic House: long live the labyrinth!

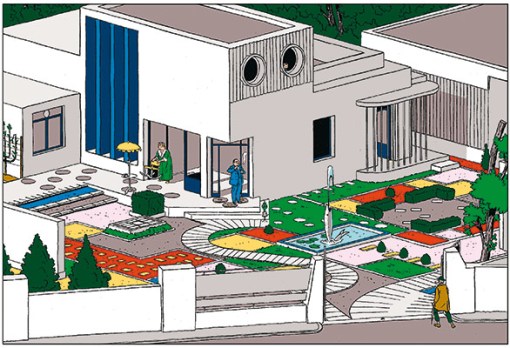

In stark and appealing contrast, we linger on the labyrinth of stairs leading Oncle to the top of his morally superior position. From his perch at the top of a healthy compost pile of cardboard, rotting planks, fluttering curtains, and shimmering metal, he can even coax a canary to sing. His knowledge of the elements, the sun reflecting off the glass panel of his perfunctory window shutter, brings things to life. Rather than leading us through the maze of our own pomp and circumstance, he maneuvers through the versatile manifestations of our globe’s interactions. No picky pebble walkway for him: just the crumbling brick beneath our feet.

In a glorious moment, Oncle demonstrates his rejection of entropy and simultaneous appreciation of decay by picking up a brick he has knocked off a picturesque pile of rubble.

Long live the organic! Long live the humorous! And long live our embrace of life being lived, by-products, inconveniences, and all.